Schwarzman Scholars worked together to create an academic journal, reflecting their ability to think critically about the Middle Kingdom and the implications of its rise. These collections of thoughts come together to form “Xinmin Pinglun,” our Journal dedicated to the publication of the informative and analytical essays of our scholars. As the application deadline for the class of 2019 is approaching and the start of the 2017-2018 academic year is on its way, we are sharing pieces from the second issue of Ximin Pinglun to give insight into the critical thinking and scholarship taking place at Schwarzman College. Here, Alexander Springer (Class of 2017) examines China’s emerging sports scene and their methods of talent development.

With the upcoming Winter Olympics in 2022, Beijing is set to become the first city to ever host both the Summer (2008) and the Winter Games, and this has led to a national push to develop sports in China. While China has long been a well-respected force in sports like table tennis, gymnastics, and martial arts, it has struggled to develop competitive athletes in other sports. As an internationally competitive triathlete and nationally competitive cyclist, I have had the chance to view China’s emerging sports scene and gain a glimpse into its sports development strategy. To develop internationally competitive athletes, China seems to be pursuing two main strategies. These include learning from international athletes and growing the number of participants in sports, in the hopes of finding previously hidden talent.

Free vacations for those willing to go rural

The amount of privilege awarded to foreign athletes in China is unparalleled. Often, races include free race entry, free lodging, free meals, and free transportation to and from the event. In one race in Xinxian in Henan province, the foreign athlete delegation was even treated to a lavish dinner complete with a toast from the deputy mayor of the county. These types of all-inclusive races tend to be in more rural areas, far away from the typical tourist attractions. By attracting foreign athletes, events can be labeled as “international” and promoters often receive more money from the Chinese government for attracting foreigners to a rural province. In many ways, this arrangement is a form of win-win cooperation between the Chinese province and the foreign athletes who benefit. However, what often goes unreported is that most of these foreign athletes are simply expats who work in China and are looking for a free vacation. Most of them are not competitive enough to be in contention for the prize money and some even drop out of the race due to time cut-offs or lack of fitness. However, for the purposes of the race promoter and the local government, as long as the media captures pictures of the foreign athletes on the starting line, it is not as important where the athletes finish in the race results. Furthermore, some Chinese athletes gain additional confidence by beating the foreign competitors.

Price premium for foreign ski instructors

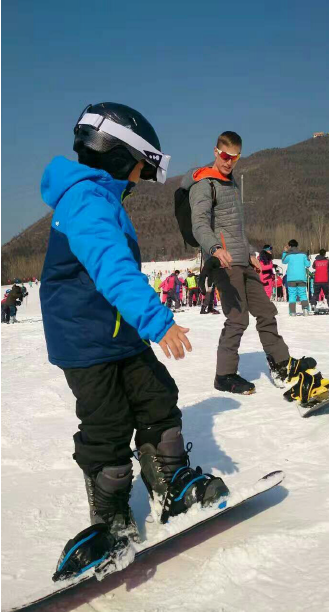

The practice of internationalizing sports can also be seen in the ski industry. This year I taught ski lessons to Chinese children. While teaching, I witnessed the price premium paid for foreign ski instructors. There were a plethora of local Chinese ski instructors who spoke Mandarin fluently and by many measures, were effective ski teachers. However, the foreign ski instructors commanded an hourly teaching rate two to three times as much as the Chinese instructors despite not speaking the language and having no ski teaching certifications. When the parents of students were asked why they sought foreign instructors for their kids’ ski lessons, they often cited their belief that foreign skiers were better than Chinese skiers. Furthermore, parents mentioned that foreign teachers can also teach their children English in addition to skiing.

An overlooked problem to this thinking is the fact that learning a new skill like skiing becomes much more difficult when it is taught in a foreign language. Even more problematic is the perceived inferiority of Chinese ski instructors compared to their foreign counterparts. While many of the instructors lack the big mountain, off-trail terrain and steep slope experience that many foreigners gathered from their home countries, they are more than qualified to teach in the beginner and intermediate slopes found on most mountains in China. Until the Chinese mindset shifts to believe in the ability of their home-grown talent, foreign ski teachers will continue to experience significant privilege on the slopes.

Ready to grow: China’s emerging sports scene

Overall, China’s national strategy of developing its sports culture is starting to yield results. The acquisition of the Ironman triathlon series of races by Chinese conglomerate Wanda Group led to some of the first large scale triathlons in China. Two world-championship qualifying half-Ironman distance races were produced by Wanda in 2016, attracting more than 1,500 athletes each from over 50 countries, with another five races planned for 2017. Triathlons are a good pulse-check for the emerging sports scene in China as the international athletes who come to compete in races largely dominate the professional and amateur fields. However, in each race there are some notable Chinese athletes climbing the ranks and many more aspiring athletes who are investing large amounts of money into equipment, coaching fees, and anything else to gain a competitive edge. In the inaugural Hefei half-Ironman triathlon in 2016, there were nearly 1,000 Chinese athletes, of whom over 700 were racing their first triathlon. If these athletic trends continue, the next generation of Chinese athletes will likely be a competitive force on the world stage.

进口的竞争:中国新兴体育市场领域的外国特权 (司马安德)

2008年夏季奥运和2022年冬季奥运在北京的举办,为中国投资体育产业的基

础设施和运动员发展注入了新的动力。作为培养有竞争力的运动员的目标的

一部分,中国正通过向国际优秀运动员学习和增加体育运动员数量两种方式

来实现。这种方式为在中国服役的外国运动员带来了特权,包括自由的比赛

假期,冬季运动的外国教练的价格溢价,以及对国外举办的体育赛事的强烈

兴趣等。

Alexander Springer (Class of 2017) is from the United States of America, and graduated from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.